TravelPerk kicked off the year with some big news: The late-stage corporate travel tech startup raised $200 million and acquired another company.

Both developments were wrapped into a single announcement that exemplifies a major trend in travel tech right now: A surge in acquisitions by private-equity backed software companies.

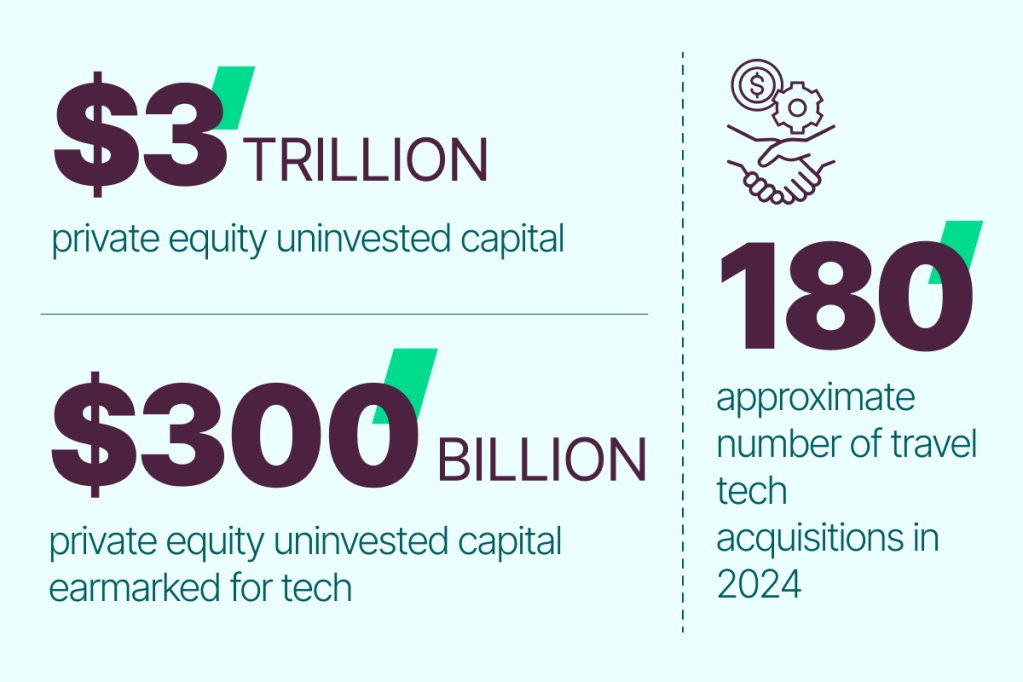

Private equity firms have accumulated an estimated $3 trillion that they need to deploy, and roughly $300 billion of that is earmarked for tech, according to investment banks we spoke to. These private equity firms have been leading large fundraises for late-stage startups that are working to modernize behind-the-scenes software that powers the travel industry. And those startups are deploying that newly raised capital to grow their businesses organically and via acquisitions.

Investment bank AGC Partners says these PE-backed players are going on a “feeding frenzy” to acquire smaller companies and consolidate their respective markets. AGC Partners estimates that there were roughly 180 M&A deals in travel tech last year, accounting for roughly one-third of all tech deals. That number has been steadily increasing since the low of roughly 77 deals in 2021.

“This is by far the biggest year that the space has ever seen from a transaction perspective in terms of count,” said Jonathan Weibrecht, partner at investment bank AGC Partners.

We’ve spoken to nearly a dozen founders and CEOs of companies that secured large fundraises over the last year, and nearly all of them have said M&A is on the radar. Investment bankers and private equity investors say they’re expecting an even busier year in 2025.

Driving the action: Tech systems need upgrades to handle unprecedented growth in travel, and private equity firms are deploying billions to take part. In 2025, expect more consolidation as well-funded late-stage startups buy up smaller players, reshaping the industry’s behind-the-scenes infrastructure ecosystem.

“We expect to see more activity in 2025 than 2024 in terms of number of deals,” said Min Liu, managing director of the travel practice for investment bank Cambon Partners.

Private Equity Dives into Travel

Nearly every major late-stage startup platform has just raised capital or is in the process, Weibrecht said.

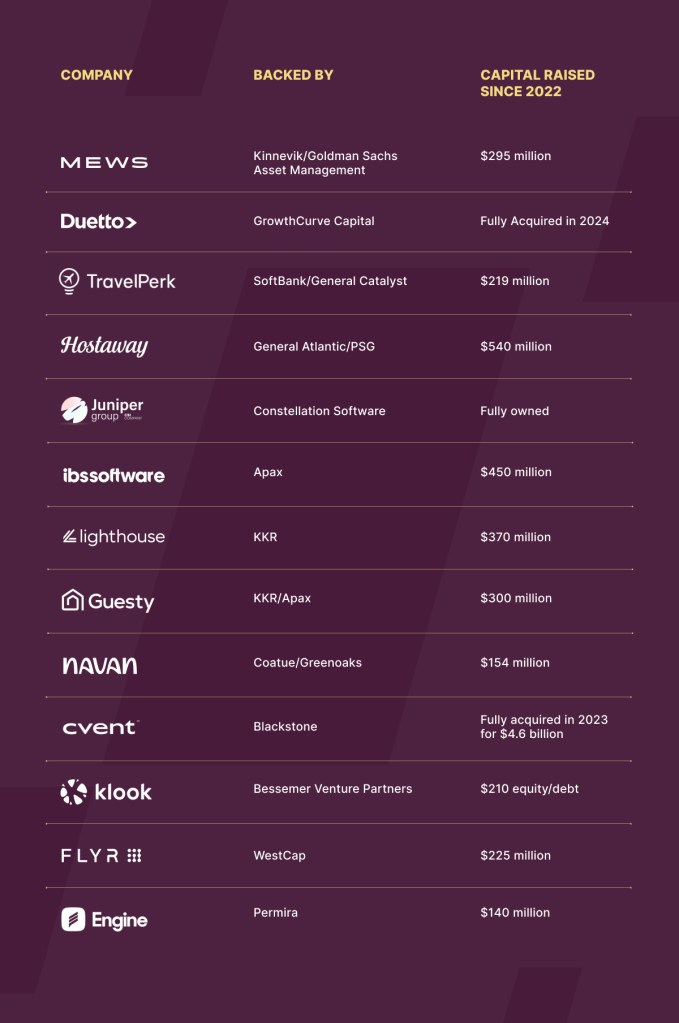

Flyr, for example, raised $225 million toward its effort to replace the decades-old airline retail infrastructure with something akin to online shopping. Lighthouse raised $370 million for a platform that helps hotels make decisions about pricing, promotion, and distribution. And Hostaway raised $365 million for short-term rental management tech.

Following that trend, there likely are more large capital raises coming in 2025.

“Private equity hasn’t really paid a lot of attention to travel much at all for a long time. I think it’s a sign of maturity within a market when you see private equity coming in,” said Laurence Tosi, managing partner and founder of WestCap. Tosi was Airbnb’s CFO for nearly three years starting in 2015 and helped Brian Chesky secure billions of dollars in funding.

WestCap led the last two funding rounds for Flyr, which has made multiple acquisitions in the past couple of years.

Background Players Take the Stage

Consumer brands like Expedia Group and Booking Holdings dominated M&A cycles last decade, consolidating the consumer market to create the giants that exist today.

Much of the activity in that space has settled, with exceptions, and the focus now is on consolidating the business-to-business tech.

About 80% of the 180 travel tech deals last year were involving business-to-business software, according to data from AGC Partners.

“Whenever you get funding, inevitably follows a period of consolidation, or movement amongst the different players,” Tosi said.

For example, Mews, a hotel tech startup, recently bought its fifth company in the past year – that makes 12 acquisitions since 2019.

Backed by private equity company Kinnivek and Goldman Sachs, with credit from Vista Equity Partners, Mews is focused on M&A as a strategy for growth, said founder Richard Valtr.

Mews is in the business of trying to modernize an antiquated piece of hotel tech, the property management system. Whether it’s Mews or Flyr or Travelperk, building these platforms and growing the client base is capital intensive — even more so now as the rise of AI forces founders to reimagine their products.

Despite so much money being available for large fundraises, early stage funding is still tight for young startups because investors are looking for companies with proven business models.

That means startups and small businesses will have a hard time investing at the level needed to upgrade tech and scale.

“That requires a lot of investment. And In order to make that investment, you need to have scale. And if you don’t have scale, you can’t make that investment, and you fall further behind,” said Akhil Chainwala, senior investment director for private equity firm Kinnevik. The firm led the last round for Mews and participated in the past few rounds for TravelPerk.

Valtr of Mews says that’s why it often makes sense for those smaller companies to join well-funded companies rather than continue independently.

“I think for a lot of providers, it’s basically a double whammy. First, they thought they could still kind of ride out the cloud wave. And now, thinking about how they’re going to ride out the AI wave is making a lot of them feel nervous. So I feel like that’s one of the things that is driving interest (in selling),” Valtr said.

“If you haven’t really invested into that core R&D piece of your system for a long time, it’s difficult to actually start that up.”

Nearly 40% of the travel tech M&A deals last were involving hotel tech, AGC Partners found. But the firm expects more activity in the airline tech space as new platforms push to scale.

“It’s a very attractive software market because retention is so incredibly high,” Weibrecht said.

Motivation to Grow

The investment bankers say that these PE-backed companies are going on acquisition sprees because they need to grow revenue.

AGC expects this type of strategy to continue over the next two years.

“The use of funds for all of these capital raises is to go do follow-on M&A,” Weibrecht said.

“You’ve got all these companies between $50 million and several hundred million of net [annual recurring revenue], too small to be public … probably too small for the premium-paying horizontal acquirers to snap them up. And so what they need to do is they need to go and buy revenue.”

Mews is one that will eventually get to the exit point, and that’s something its leaders have to think about. It’s still a relatively small company now in terms of market share, with several notable competitors (including market share leader Oracle Hospitality.)

“I think at our scale and our size, it’s difficult to understand who would be the potential acquirers,” Valtr said. “I think that I wouldn’t be performing my fiduciary duty if I didn’t say that we’d always look at what would be the best outcome for our shareholders and, ultimately, for our customers. So I think if we could also go towards an IPO, I think that would also be a great mark.”

Who’s Selling

The selling price for most of the deals in 2024 was undisclosed. That often — but not always — means the deals were small.

“Private equity hasn’t really paid a lot of attention to travel much at all for a long time. I think it’s a sign of maturity within a market when you see private equity coming in.”

Laurence Tosi, WestCap

It’s more of a consolidation of fragments, with buyers looking to add clients or geographic coverage, improve tech, or add a group of new employees. The sellers are often companies generating between $5 million and $50 million in annual recurring revenue, AGC said.

“A lot of what we like to do with our companies is what we call strategic bolt-on acquisitions. So they’re not necessarily transformational, but they’re adding a product set they didn’t already have,” Tosi said.

The sellers are often smaller startups that made deals before the pandemic and are now having a harder time securing venture capital. If they’re struggling to get to the next stage, now is a good time to exit.

Baby Boomer founders are another group of sellers, looking for an exit as they prepare to retire. They often have small, independent businesses — like corporate travel agencies or old hotel tech — with loyal customers.

Juniper Group is open to hearing from them. The company plans to buy as many as a dozen travel tech companies this year, according to Jaime Sastre, CEO of Juniper Group.

“Next year, we’ll do more, and the next one, we’ll do more,” Sastre said.

While the company isn’t backed by private equity, it has jumped full force into the travel M&A market. Sastre formed Juniper Group in 2020, and it now has 31 companies, including around a dozen in travel.

Juniper Group is an operating portfolio of Vela Software, one of the six divisions of Toronto-based Constellation Software, which owns more than 1,000 companies. It has an unusual model: It buys small travel tech companies, grows their revenue, and then uses that revenue to grow organically and buy more. Unlike private equity, which typically sells portfolio companies after about five years, Juniper Group plans to “never” sell any of its companies.

Juniper Group would be buying regardless, Sastre said, but he thinks the market has eased a bit since the pandemic. The companies that survived are growing again.

“It’s a good moment probably to sell because they suffered Covid, they’re revamping now with that growth and better profitability, and it’s probably a good moment for them to to get out and for others to get in,” Sastre said.

He said Juniper Group often appeals to owner-operators ready to step away from such heavy responsibility while also continuing to run the company. Because Juniper never sells, the stakes are a bit different.

“We don’t care about how much our companies are worth. All we care about is how much return are we getting from those companies, and what’s the future in terms of financial growth of this company.”

Moving Money

While middle market companies are leading the charge, there’s plenty of activity elsewhere.

Travel corporations, finally seeing substantial recovery post-pandemic, are deploying their own capital into growth initiatives. Amadeus, for example, made two big purchases.

Despegar plans to sell to tech investment firm Prosus for $1.7 billion.

And there will always be companies changing hands in big private equity acquisition deals. Cvent, for example, was fully acquired in 2023 for $4.6 billion. “At some point in time, you need to change the profile of your investors who can continue your company’s journey for the next stage of growth,” Liu said.

And for a similar reason as the buildup of private equity, Liu suspects there could be IPOs in the near future from travel companies who have been talking about it but haven’t pulled the trigger.

The parent company of Hotelbeds, for example, just said it’s planning an IPO at a valuation of $5.1 billion.

“Very strong landmark deal this year — the first one to watch,” Liu said.

“This is a case where investors held because of Covid. You will see that the financial performance has been very, very good post-Covid. Now is a good time to go to market again, and the IPO market is opening.”

Regulatory Hurdles

For any large deals, there’s the issue of regulations to watch out for. And that may be a deterrent, Liu said.

Industry leaders suspect there may be relaxed regulation around M&A in the U.S. under the new presidential administration. But large deals often are subject to EU approval, as well, and that can cause deals to fall apart.

Booking Holdings was blocked from buying eTraveli Group for that reason. And it’s unclear whether Amex GBT will be allowed to purchase CWT. It’s not in the travel space, but the Trump administration has already sued to block Hewlett Packard Enterprise from acquiring Juniper Networks (unrelated to Juniper Group).

That means traditional acquirers, like Google and Booking Holdings, need to take precautions before attempting deals.

“Booking — really, any type of deal is difficult because of this regulatory scrutiny,” Liu said.

“I don’t see very, very large deals happening in this space in the coming years. For large deals, for mergers of equals, there will be increased scrutiny from regulators.”

But smaller companies, the ones dominating the cycle now, likely won’t need to worry about that.

“It’s very active in the small, mid-sized deals because there’s a lot of market interest and investor interest to build platforms. So they are the main driving force of the activity on the market currently,” Liu said.

Navigating the Risk

While there is a lot of consolidation happening, acquisitions come with a level of risk and consequence that some don’t believe is worth it.

Adam Harris, CEO of hotel tech company and Mews competitor Cloudbeds, told Skift last year that M&A hasn’t been a growth strategy for his company — though that could change in the future.

He believes the process can create a bad experience for clients. And, the cost of integrating them takes away from resources that the company would use to improve the product.

“We’ve seen other companies roll up players similar to them, but we haven’t necessarily seen that followed by a tremendous amount of organic customer growth. This makes us wonder how well that horizontal strategy is working for hoteliers,” Harris said.

“The use of funds for all of these capital raises is to go do follow-on M&A.”

Jonathan Weibrecht, AGC Partners

Although Flyr has made multiple acquisitions over the past two years, Flyr CEO Alex Mans said it’s not an easy process to undergo because it often means integrating different company culture, products, and geographies.

“It’s always much harder than you think it’s going to be,” Mans told Skift last year. “I’m still very fortunate that we were able to aquire great companies with great people that are really helping us grow and accelerate the business. But that, too, is also harder and more difficult than you think it is when you do it.”

Building a company via acquisition also doesn’t guarantee it’ll turn out successfully. Look at travel agency tech company Mondee, which just filed bankruptcy after acquiring five companies in 2023.

Still, Valtr of Mews believes it’s a good way to more quickly move the industry forward.

“I think that people tend to see M&A as this terrible thing. It doesn’t need to be this negative perspective: These are private equity companies that are going to come in and just try and milk the customers as much as possible,” Valtr said. “You can still be a fast-scaling, product-first company, and still also be wanting to liberate the rest of the market from these legacy solutions.”

Illustration credit: Vonn Leynes/Skift

Stay Ahead of the Megatrends With The Daily

Skift’s morning newsletter delivers breaking news, features, and exclusive analysis from around the world straight to your inbox, five days a week.